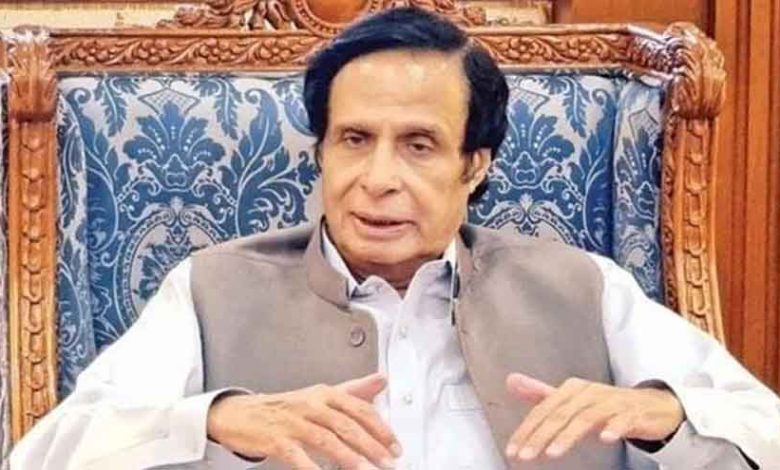

Parvez Elahi is granted a court exemption from appearing in the matter of illegal hiring.

Chaudhry Parvez Elahi, the former chief minister of Punjab, was granted a one-day exemption from making a personal appearance by the Anti-Corruption Court in Lahore on Wednesday.

The case against Elahi and others pertaining to alleged unlawful recruitments in the Punjab Assembly was heard by Judge Javed Iqbal Warraich of the Anti-Corruption Court in Lahore. Tanveer Chaudhry Advocate, a government attorney, was in court.

The court granted Elahi’s lawyer’s plea for a one-day exemption from appearance during the hearing, citing his client’s illness.

Haider Shafqat, Zohaib, and co-accused Ijaz all entered acquittal pleas in the meantime. The court requested arguments for the upcoming hearing and sent alerts to the anti-corruption authorities.

Similarly, the court requested legal reasons at the subsequent hearing about co-accused Mukhtar Ranjha’s acquittal plea.

The court subsequently postponed the case’s remaining proceedings until October 8.